Junior may have been a close-to-unanimous selection to Cooperstown this week, but his namesake video game was even more prolific.

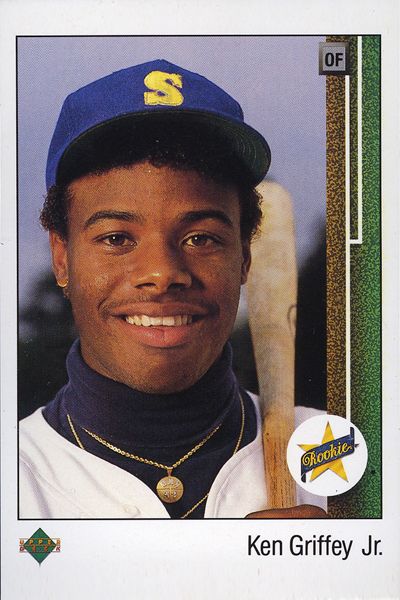

Like Andy Dufresne, Ken Griffey Jr. crawled through a river of shit of the PED era and came out clean on the other side. He was duly rewarded Wednesday with a close to unanimous election to baseball’s Hall of Fame in spite of a decade of injury and failing to hit .260 or better eight of those final 10 years. From ‘01-’10, Junior played fewer than half of the possible games and during his career never sniffed the bunting in October, only advancing beyond a division series once (1995).

He does, however, enter Cooperstown as a 13-time All-Star, a 10-time Gold Glover and the 1997 AL MVP. Plus he got me started on wearing the hat backwards and coveting Upper Deck Series 1 cards. Hello turtleneck and chain(s).

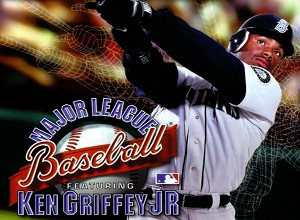

Great credentials, all around. But where Junior really deserves credit for innovation and pushing the boundaries is in regards to MLB video game play on his namesake release for the Nintendo 64.

Great credentials, all around. But where Junior really deserves credit for innovation and pushing the boundaries is in regards to MLB video game play on his namesake release for the Nintendo 64.

From the passable and nostalgic RBI Baseball to the totally confounding and ultimately ill-fated MVP Baseball (which was mercifully dragged out to the leach field behind the EA campus and drowned in an inch and a half of standing sewage in 2008), getting a baseball game right for a video game console is like asking Tom Hanks to reprise the haircut he had in The Da Vinci Code. In other words, some things only (thankfully) come around once in a lifetime.

Major League Baseball Featuring Ken Griffey, Jr. is that once-in-a-lifetime game. Developed by Angel Studios—which later became Rockstar. Yes, the studio that brought you Grand Theft Auto IV, (at the time of its release, GTA IV earned $310 million in its first day and US $500 million in its first week making it the quickest-earning form of media, ever) Grand Theft Auto V, Max Payne 3 and Red Dead Redemption.

Here are four things that made the game an all-time great:

• No load time/rapid speed of play: Pop in the cartridge and go. There was no spinning wheel (or baseball) to wait for the thing to think—just the Angel logo, the crack of the bat and then this incredible Ken Griffey Junior Rap (it goes: Call me Junior. Call call call me Junior. C-c-c-call me Junior over a hip hop beat and some seventh inning stretch pipe organ). Every time I get nervous like when I get pulled over or am filling out the misdemeanors and felonies part of a job application, I find myself a stuttering mess/whispering Call me Junior, c-c-c-c-call me Junior to myself Max Headroom-style.

Once in-game the speed of play is surprisingly smooth. It is as if those future Rockstar coders honed the quick sensibility of carjacking, stabbing hookers and running over pedestrians on America’s Pastime. Part of it is the intuitive and, um, provocative—not to mention ergonimically sound N64 controller (see: last bullet) which was seemingly made for a baseball game. Part of it is the simplicity of the game structure: Instead of trying to get facial ticks right and every individual tug and pull down, the game simply rated each position player using five stats: batting, power, speed, defense and arm. Pitchers got three: speed, stamina and control.

The streamlined-but-effective nature of the game was also reflected in the ease and speed of play. There were few to no pauses or refreshes or reload/reset time between pitches or at-bats and that meant a 1-2-3 inning could take under 40 seconds.

• The 1998 Cleveland Indians: The game was released on May 31, 1998. I met my buddy Sudha for the first time that summer when he came over to my house in Oakland to play Griffey and drink 40s. I’d never met this kid, therefore, had never played video games against him. I was the Giants and he was the Indians and he just fucking smoked me right out of the gate. Nobody ‘gets’ a baseball game that quickly—nobody but for Sudha. He was like a savant. I turned to our mutual buddy Paul who introduced us and said, “It’s too bad That’s Incredible! isn’t on anymore because this kid would have his own segment. And it would say like, ‘Incredible 40-drinker/Griffey Player’ at the end.”

After that night, a few more months of gameplay passed before I came to the conclusion that the 1998 Cleveland Indians on Griffey would be one of the more unstoppable forces in the annals of sports video games akin to Tecmo Super Bowl Bo Jackson, Super Macho Man’s haymaker, E. Honda’s Hundred Hand Slap …or the moves of any of the Ikari Warriors.

Check this lineup:

1 C Sandy Alomar

2 1B Jim Thome

3 2B David Bell

4 SS Omar Vizquel

5 3B Travis Fryman

6 LF Brian Giles

7 CF Kenny Lofton

8 RF Manny Ramirez

9 DH David Justice

What the FUCK man??? That’s fucking insane!! I still look at that lineup (at least six have arguments for being in the Hall) and am like how did the Yankees win it all that year (beating Cleveland in the ALCS) and how did they not just give the Indians a pair of honorary Commissioner’s Trophies after the season: One for being that bad-ass on paper and the other for having a catcher (an Alomar brother at that) bat lead-off.

• Pitching (and batting and fielding): Like the percentage of voters who gave Junior the nod his first time on the ballot, more than 99 percent of MLB-themed video games have one fatal flaw: Pitching. It’s either the computer doing what it wants to (think Bases Loaded) or the computer forcing you to throw in a strange moving box with no discernible difference between a fastball and a changeup, EVERY pitcher’s curve having the same giant Zito arc—and none of the pitchers (think knuckleballers throwing fastballs mid-90s) are similar to their actual motions or throw their actual specialty pitches. Don’t even get me started on the lack of difference in the stretch.

Junior’s game was different. Pitchers, according to their actual skill set, could throw a fastball, a breaking ball (including a curve a slider and a screwball) and a changeup. Players also had a “special” pitch option (splitter, cutter or knuckleball). Each pitcher threw his actual specialty pitch and would tire, just like in real life. It was insanely accurate for being so simple.

Batters used the controller’s toggle stick, which was very similar to, well, actually swinging a bat. A looping motion would result in a inside-out swing, good for opposite field home runs. A straight up and down cut would result in sharply hit ground balls. The batting target (a moving circle where the ball was thrown) would grow or shrink depending on the (again, accurate) prowess of the actual hitter. Getting the circle over the sweet spot of the bat and hitting the swing button as the pitch crossed the plate would yield the best results. Swinging the bat in this game was the second-most intuitive thing I’ve ever done with my hands in my life.

• Intuitive use of the whole controller: Even though this looks like some kind of adult toy that should be called The Shocker II (it even had a vibrating attachment for Chrissakes), beyond self-pleasure this thing was pretty much designed for a baseball video game. The Z (or trigger) button was great to fool side-glance-sneaking/sign-stealing opponents into thinking you were throwing a fastball (when you were pretending to press the top or A button in plain sight…) and the throwing to the bases—which video game baseball NEVER got right (“I was throwing to fucking third. THIIIIIIIRRRRD!” as the ball skips from left field to first base and two runs score) was never simpler. There is a diamond shape cluster of four yellow buttons in the upper right-hand part of the controller called the ‘C’ buttons and each button corresponded with a base. FUCKING GENIUS.

• Intuitive use of the whole controller: Even though this looks like some kind of adult toy that should be called The Shocker II (it even had a vibrating attachment for Chrissakes), beyond self-pleasure this thing was pretty much designed for a baseball video game. The Z (or trigger) button was great to fool side-glance-sneaking/sign-stealing opponents into thinking you were throwing a fastball (when you were pretending to press the top or A button in plain sight…) and the throwing to the bases—which video game baseball NEVER got right (“I was throwing to fucking third. THIIIIIIIRRRRD!” as the ball skips from left field to first base and two runs score) was never simpler. There is a diamond shape cluster of four yellow buttons in the upper right-hand part of the controller called the ‘C’ buttons and each button corresponded with a base. FUCKING GENIUS.

I never quite figured out what the C button did on any other N64 game besides maybe catch crumbs.

…And finally, we can’t forget home run derby. Even though Griffey was never caught with or accused of using PEDs, this game was released smack-dab in the middle of the steroid era and it was just incredible to watch guys like Bonds, Piazza, Sosa, McGwire, Biggio, Canseco, Mo Fucking Vaughn, Manram, Belle, Canseco, Castilla and Galarraga mash in derby mode.

Hell, Junior in real life hit 56 dingers that year and can belt 56 in the first two outs of his game’s home run derby. And you could also choose from all 30 stadiums; there’s nothing like a nighttime home run derby at Candlestick, bombs over the South Side at the old Comiskey, the hermetically sealed vaults of the Metrodome, the Astrodome or Griffey’s own artificial backyard, the Kingdome to act as my field of pixilated dreams. One of the biggest regrets of my life is having not made it up to Olympic Stadium in Montreal in time to enjoy a Molson and some Poutine at an Expos game. Playing there in Griffey is a close second.

Of all the drunken nights drenched in pint foam and bad conversation with fog horns staving off the morning light I spent in my 20s living in the Bay Area, playing Junior with my two buddies stands alone as the one I’d want back.

That is why my vote is for Ken Griffey Jr.’s turtlenecked bust to display a N64 logo above the brim of his turned-backwards cap when he becomes immortalized in July.

C-c-c-call me Junior.