We learned last week the good old days of the NFL were just as bad if not worse for a player’s health. The league built its tough-guy image on a hit that Frank Gifford was on the receiving end of in 1960. A hit that forced him to take a year and a half off and prompted his family to have his brain studied by the Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University. The hit is both a part of the NFL’s lore and current marketing. And while NFL commissioner Roger Goodell gives lip service to honoring players like Gifford with the continued study, the reality is more will die faster as the NFL fights their lawsuits.

By Andrew Pridgen

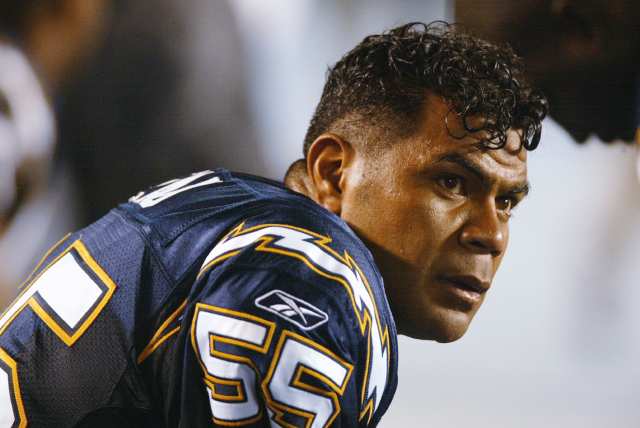

NFL great Frank Gifford’s family wanted to honor his legacy by having his brain dissected. And what they found was the same diagnosis fellow hall of famers Junior Seau, John Mackey and Mike Webster share. In fact, 87 of the 91 brains from dead NFL players studied by the Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University show signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, better known as CTE.

“We decided to disclose our loved one’s condition to honor Frank’s legacy of promoting player safety dating back to his involvement in the formation of the NFL Players Association in the 1950s,” the Gifford family statement said. “His entire adult life Frank was a champion for others, but especially for those without the means or platform to have their voices heard.”

Gifford, the son of an itinerant oil driller, claimed his family was forced to move 29 times before he graduated high school because his father could not find nor keep work during The Depression. He took a year after graduating Bakersfield High School to play for the local junior college before gaining admission to USC where he ran for 841 yards on 195 carries during his senior campaign earning All-American honors. His professional playing career spanned a dozen years as a defensive back, running back and flanker (he made the Pro Bowl at all three positions) for the New York Giants. He is best remembered off the field for his almost three decades of play-by-play announcing for Monday Night Football, think the Century 21 blazer era.

Gifford’s style under headset was as straightforward and knowledge-rich as his playing time—the most monochrome color guy in the business: “So many of us, especially in these high-pressure, high-profile businesses, there’s a tendency to have these knee-jerk responses to things,” booth mate Al Michaels said. “That was never Frank. Frank was always the guy who would assess it. He would do it quietly. Then he would very often have something on the back end, when everything had calmed down, that was well thought out.

“Frank never wasted any energy flying off the handle.”

It came as a surprise then to Michaels along with many of Gifford’s colleagues that behind closed doors he silently suffered the effects of CTE. But it shouldn’t have. Though Gifford was said to have died of natural causes in early August at the age of 84, symptoms of the degenerative brain disease linked to head trauma were prevalent according to family members and close friends. CTE has been identified as a root cause for diseases like Alzeheimer’s and depression and signs of memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment and impulse control problems are chief indicators for those who suffer.

Gifford’s playing career was defined by a hit that ushered in the modern-day marketing of brutality that defines the NFL. Think all the grandiose gladiator music rising underneath the baritone of Jefferson Kaye or Harry Kalas superimposed with the slo-mo spiral aesthetic we’re fed from the cradle—leading back to a single play 55 years ago.

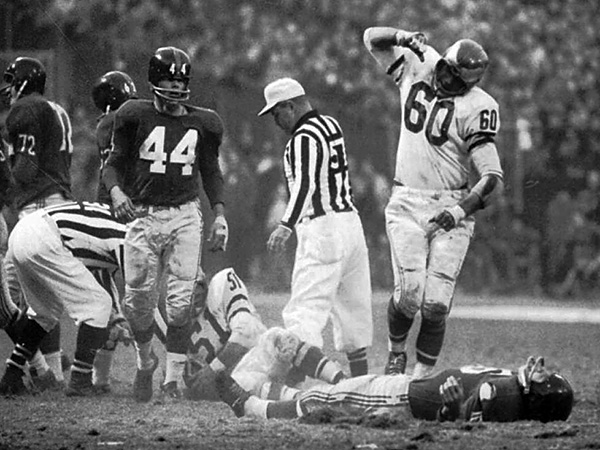

On Nov. 19, 1960. Gifford caught a pass over the middle in sub-zero temperatures inside Yankee Stadium. He tried to tiptoe on the frozen field when number 60 Eagle linebacker Chuck Bednarik comes into frame in hot pursuit.

In a move akin to swerving a car into a ditch to avoid hitting an oak, Gifford cuts back to scamper out of Bednarik’s grasp. Bednarik reaches back reminiscent of a basketball center throwing his arm across the lane for an intentional foul. This move resulted in the pair colliding straight up, their upper torsos and shoulders mash and Gifford goes down like he was administered anesthesia during the exchange.

Gifford hits the ground like a paint bucket dropped from a third-story scaffold. The hit didn’t afford him the moment to float in suspended animation over the tundra. Instead, he fell fast as if he was late for a meeting with the ground. The whole of his body disappears for a moment and he’s just a pile of uniform and dirt for the equipment guy to clean up. While Gifford was indeed concussed and knocked unconscious, it wasn’t from the force of the initial hit. Gifford was hurt because his head whiplashed against the concrete-like turf.

The resulting head injury forced Gifford to retire from football in 1961. Though he did eventually return for two additional seasons at a flanker position, the player and the man were never the same.

“I do think that Mr. Gifford is a very important case for awareness,” said Chris Nowinski, executive director of the Boston University-affiliated Concussion Legacy Foundation. “The family didn’t have to do this study to explain away behaviors or actions. They truly did it to raise awareness because they silently suffered.”

NFL commissioner Roger Goodell in a released statement last week said “work will continue as the health and safety of our players remains our highest priority. We have more work to do—work that honors great men like Frank Gifford.”

Garrett Webster, son of late Pittsburgh Steelers lineman Mike Webster who died from a heart attack at only 50 in 2002 called bullshit.

His father’s post-playing days were marked by erratic behavior, family members say. Webster was the first NFL player to be diagnosed with CTE and his family has long been outspoken against the disease that has always defined the game. “I used to think that donating your brain was helping the game become much safer, but now I believe the NFL just does not care,” he said in an email to the Los Angeles Times.

“During the last years of his life Frank dedicated himself to understanding the recent revelations concerning the connection between repetitive head trauma and its associated cognitive and behavioral symptoms—which he experienced firsthand,” the Gifford family’s statement said. “We…find comfort in knowing that by disclosing his condition we might contribute positively to the ongoing conversation that needs to be had.”

The families of players diagnosed with CTE after death can be eligible for up to $4 million depending on time served in the league, age at diagnosis—and whether the league’s lawyers fight the settlement.

“I saw the best of Frank,” Michaels said in light of the news. “You never know what’s going on in somebody’s brain.”

Until you do.

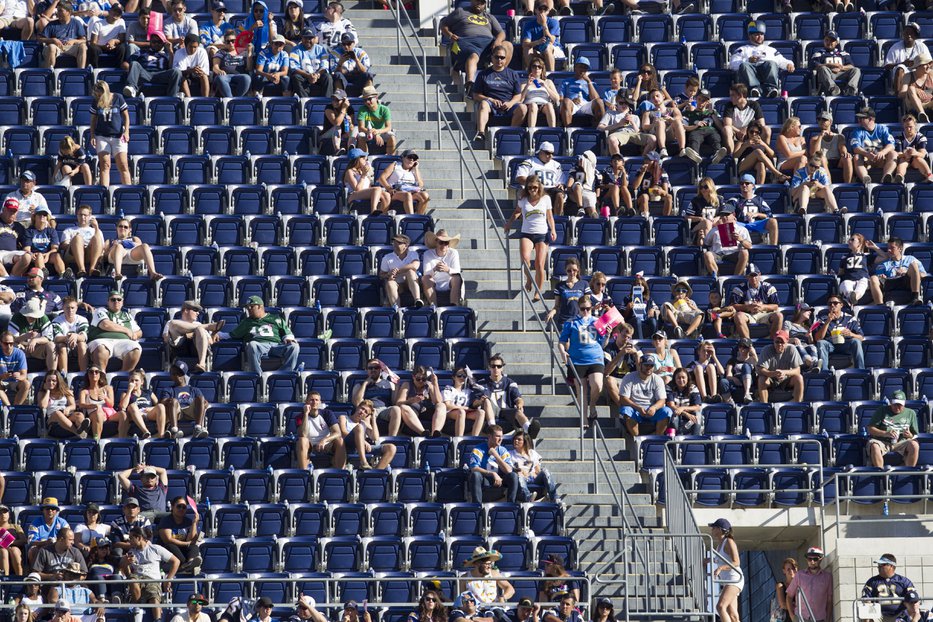

Who can you ask to screw off when he wants your city to spend money it could be using to build parkways, parklets, beaches and amphitheaters?

Who can you ask to screw off when he wants your city to spend money it could be using to build parkways, parklets, beaches and amphitheaters? Who can you make a laughably ungenerous offer to when they want to see what the public can do to help out with the new digs they’d like to make billions of dollars on without spending their own money?

Who can you make a laughably ungenerous offer to when they want to see what the public can do to help out with the new digs they’d like to make billions of dollars on without spending their own money?